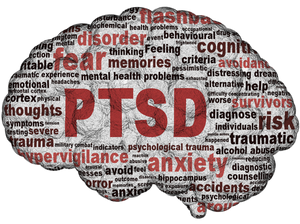

Today we are very aware of the many mental health conditions a serving soldier can suffer.

Anxiety disorders.

Depression.

Interrelationship of mental health issues.

PTSD.

Schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

Stress.

Substance use disorders.

Suicide.

Armed forces and mental health.

- 4% reported probable post-traumatic stress disorder.

- 19.7% reported other common mental disorders.

- 13% reported alcohol misuse.

- Regular soldiers deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan were significantly more likely to report alcohol misuse than those not deployed.

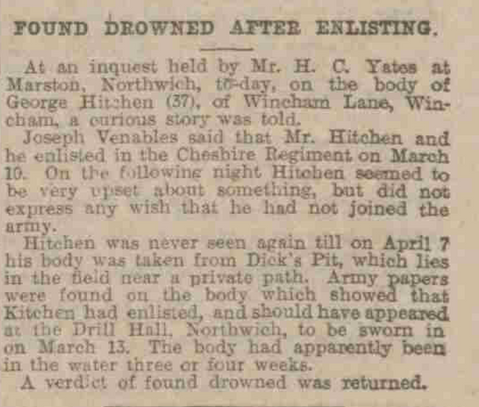

In 1916, a young British private in northern France wrote home to his parents explaining his decision to take his own life. A survivor of the early days of the Somme, considered one of the most brutal battles of the First World War, Robert Andrew Purvis apologised to his family before praising his commanding officers and offering the remainder of his possessions to his comrades. Purvis’s surviving suicide note remains one of the only documents of its kind from the First World War.

At the turn of the 20th century, suicide was often regarded as a symptom of mental illness. Cases of suicide, if recorded at all, were almost always marked as being a case of “temporary insanity”. Britain stood at the forefront of treatment for conflict-related mental illness as the Craiglockhart War Hospital in Edinburgh became famous for treating shell-shocked soldiers.

The hospital evolved to advance the fledgling understanding of conflict-related psychosis and specialised in practical recovery techniques including sports, model-making, writing, photography and the “talking cure” pioneered by psychologist William Rivers.

Due to the stigma, controversy and inflammatory nature of the topic, discussions surrounding mental health and suicide in the British military were limited for much of the 20th century. Victor Gregg, a serviceman in the Second World War, recounted in an interview in 2015 how psychological aftercare for demobilised men in 1945 was non-existent, lamenting, “My brain was filled with images of suffering that were to haunt me for the next 40 years… The final gift from a grateful country was a civilian suit, a train ticket home and about £100 of back-service pay.”

Sixty-four years later, fortunately much has changed. At the turn of the 21st century, both the military and governments in the UK have come to recognise the issue of military-related suicide.

But despite the increase in mental health awareness and support campaigns for both serving soldiers and veterans over the past two decades, concerns over deaths continue. The Ministry of Defence spends £22m a year on mental healthcare for veterans, with a further £6m annually for support within the NHS. But military charities argue that this is not enough – particularly as focused statistical recording and analysis of veteran suicide cases only began in earnest after 2001.

In March 2019, Scottish warrant officer Robert McAvoy, a veteran of 20 years service, took his own life. The following month 18-year-old Highlander Alistair McLeish died by suicide at Catterick Garrison in York. These tragedies are by no means unique.

In 2018, research by a Scottish newspaper demonstrated that a former member of the forces takes their own life in Scotland every six days. This prompted the Scottish mental health minister Clare Haughey to publicly pledge closer consideration of the mental healthcare of Scottish soldiers and veterans.

Concerns over the suicides of 71 British veterans and serving personnel in 2018 led UK defence secretary, Tobias Ellwood, to tell ITV News, “I’m truly sorry. I’m sorry that they feel the armed forces, NHS and government have let them down.” This was not an admission of responsibility for a lack of duty of care. It was a poor excuse for an apology which undercut the severity of the issue and role of the establishment within it, by insinuating that the “lack of support given” was a matter of perception. However, Ellwood also admitted: “We must improve.”

Military service and veteran suicide are not new issues, but there are crucial conversations to be had about the subject publicly, politically, socially and medically. Claiming there is a suicide “epidemic” would be an exaggeration as the numbers do not support that kind of term, but the issue remains pertinent and in need of public attention.

Bluntly, men and women have died, are dying and will continue to die if society does not examine the issue of military suicide.

Only through open discussion, active research and recognition of service and veteran mental health-related deaths can these tragedies be prevented in the future, my issue is it's taken 100 years for action to be taken.

The veterans’ mental health charity Combat Stress is available 24 hours a day on 0800 138 1619 for veterans and their families; 0800 323 444 for serving personnel and their families; via text on 07537 404719; or at www.combatstress.org.uk.