Williams parents were Charles and Ann Millington. Charles was working at Marston Salt Mine as a Salt Maker, with the eldest son James, noted in the 1891 census as a Salt Miner at the tender age of just 15 years.

By 1901 the family were living at 6 Cross Street, Marston, and William was aged 12 years. When you study each census, it becomes clear a number of children had died between the ten-year census periods.

In 1908, Williams father Charles died aged 56 years, and in 1911, Ann Millington and four of her sons were now living at 32 Ollershaw Lane, all the sons working at the salt mine. The 1911 census contains more information, and one of the requirements was for the head of the household to list all children born to the marriage, Ann Millington has written; Children born 14, Living 9 and died 5.

William Millington married Mary Jane Taylor in 1909, and records show Mary Jane's maiden name was Micklewright, therefore she had been married before and had four children born between 1894 and 1905 all with the last name Taylor, with a further child born in 1909, but this time with the last name Millington, the same year she married William Millington.

In 1909, William was aged 19 when he married Mary Jane, with Mary Jane being 18 years his senior at aged 37 years of age.

By 1911, William had left Marston and was staying with his father-in-law Benjamin Micklewright in a large seven roomed house in Crewe. Benjamin Micklewright was an Engineer. William Millington is a 'Sowing Machine Agent'. William's wife Mary Jane, is living in Earlestown, Lancashire, and she is also a Sowing Machine Agent. I feel it's safe to presume William was just staying with his father-in-law rather than living there.

Mary Jane was living with all five of her children, the youngest Charles Fredrick Millington was aged just 2 years, almost certainly named after Williams father Charles Millington who died the same year he was born. The four other children having the last name Taylor, and clearly written in the 1911 census. The house had six rooms, which could be considered large by the standards of the day. The family appear to be doing fine, and by 1914 and the outbreak of the First World War, they had moved to 17 Woodstock Street, Oldham,but things were about to change.

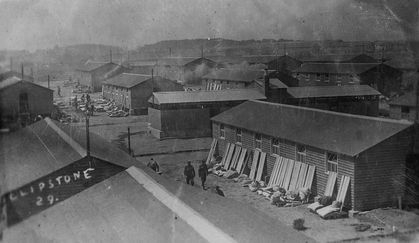

Clipstone Camp was a massive army camp of wooden huts which was built at Clipstone near Mansfield in WW1. While this camp was just one of those built to train the men of Kitchener’s New Army, it is believed to be the largest.

Clipstone Camp could hold upwards of 30,000 men. Men of the UPS (University and Public Schools Brigade) were the first to arrive in May 1915. Over the next four years, men of many regiments came to the camp. The once peaceful countryside was alive with soldiers digging trenches, practising on rifle ranges and stirring up the dust on country lanes as they went on training marches.

“I had a little bird

its name was Enza.

I opened the window,

And in-flu-enza.”

Young adults between 20 and 30 years old were particularly affected and the disease struck and progressed quickly in these cases. Onset was devastatingly quick. Those fine and healthy at breakfast could be dead by tea-time. Within hours of feeling the first symptoms of fatigue, fever and headache, some victims would rapidly develop pneumonia and start turning blue, signalling a shortage of oxygen. They would then struggle for air until they suffocated to death.

Hospitals were overwhelmed and even medical students were drafted in to help. Doctors and nurses worked to breaking point, although there was little they could do as there were no treatments for the flu and no antibiotics to treat the pneumonia.

During the pandemic of 1918/19, over 50 million people died worldwide

and a quarter of the British population were affected. The death toll

was 228,000 in Britain alone. Global mortality rate is not known, but is

estimated to have been between 10% to 20% of those who were infected. More people died of influenza in that single year than in the four years of the Black Death Bubonic Plague from 1347 to 1351.

On the 28th October 1918, William was admitted to hospital suffering from the symptoms of influenza, by the 2nd November 1918 William's condition had deteriorated with pneumonia being diagnosed, and on the 4th November 1918 William passed away.

William would be the second Marston Lad to die from Influenza at a Military training camp in 1918, Herbert Shapes also died from Influenza three weeks earlier on the 11th October 1918 at Kinmel training camp.

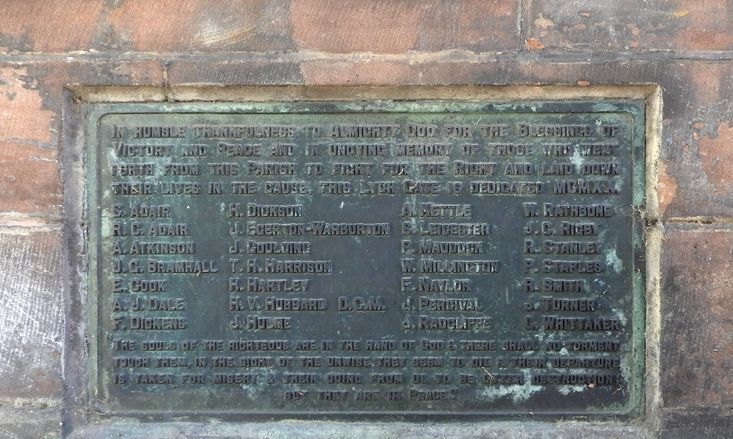

William would become the last Marston Lad, and the 30th, to die due to the First World War.

The war gratuity was introduced in December 1918 as a payment to be made to those men who had served in WW1 for a period of 6 months or more home service or for any length of service if a man had served overseas. The rules governing the gratuity were implemented under Army Order 17 of 1919.